INCLUSIVITY IN DESIGN FOR CHILDREN

The social transformation that countries worldwide have undergone over the past 35–40 years has significantly influenced and altered family structures and parental attitudes within those societies. Today, the number of children in families has decreased, and the value attributed to them has increased (Sivri, 1993). This has given rise to a type of family that could be described as “child-centric” — where children are constantly surrounded by their parents, akin to a helicopter hovering overhead, and where everything is arranged according to the child’s wishes.

Development, whose foundations are laid in the early years of life, is a process that greatly affects the individual’s later life experiences. A child’s development is shaped by two main factors: heredity and environment. The concept of “self,” which emerges as a result of the interaction between heredity and environment, is a third factor that influences later stages of development (Sivri, 1993). The environment plays a significant role in shaping children’s behavior. Physical environments for children are often designed by adults, and sometimes they are not designed at all — the child uses the environment by coincidence. Children rarely, if ever, participate in the design of their own physical surroundings, nor can they articulate the kind of environment they wish to live in. Yet the physical environment plays an active role in children’s development (Sivri, 1993). Understanding children’s development and their relationship with their surroundings is crucial to creating environments that appropriately include them (Gökmen, 2009).

Inclusive Design – Participation and Children

Design for all, also known as “Universal Design,” refers to a built environment conceived to ensure equitable use for all, offering flexibility for individuals with varying skill levels, incorporating simplicity and perceptible information, being tolerant of error, requiring low physical effort, and providing appropriate dimensions and spaces for approach and use (Mace, 1985). Through the principle of “social integration and participation,” it aims to strengthen the individual’s relationship with their environment (Evcil, 2014).

Participation can be defined as the experience of having a say, with one’s own perspective, in decisions that affect us directly or indirectly and shape our community’s life (Kaya et al., 2016). The foundation of the inclusive design approach is the “social justice and equality” ensured through participation. The right of children to participate is linked to their involvement in matters that concern them. However, for adults, children’s rights often mean only protection. True protection — ensuring physical, mental, and emotional healthy development — is only possible and sustainable if children can express their needs and demands regarding matters concerning them and play a decisive role in their own lives (Kılıç, 2015).

The elimination of the injustice children face solely because they are children, referred to in international literature as “ageism,” can only be achieved through a new perspective on children (Kaya et al., 2016). Despite directly affecting their lives, children are usually not given a say in shaping the built environment. Decisions on their behalf are made by adults, as in many other areas. However, regardless of age, gender, or origin, having a say in shaping one’s living environment is a matter to be addressed within the framework of human rights (Gökmen, 2013). In this sense, inclusive design is both a necessity and a right for children. Participation is not only a theoretical approach but also a form of practice and action.

Protecting the fundamental rights and freedoms of children, who have different characteristics and special needs from adults, in their growth and development processes is an important societal responsibility. In line with this awareness, the most comprehensive and inclusive document on children’s rights — the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) — not only defines participation as a right but also enshrines it as one of its umbrella principles (Article 12). This means that participation, along with the other three umbrella principles — “ensuring children’s survival and development,” “non-discrimination,” and “giving primary consideration to the child’s best interests” — must be considered in all rights and regulations within the Convention (Kılıç, 2015).

Article 12: States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, with those views being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child. This demonstrates that, despite differences in age and maturity levels, it is possible to establish a structure in which children can make decisions alongside adults. The task is not to separate, exclude, or discriminate against children based on assumptions about their inability to participate due to age or maturity, but rather to adapt and transform the structure to create participation opportunities suitable for each child’s unique characteristics (Kılıç, 2015).

The development of children’s participation skills is directly related to the opportunities provided to them. The earlier and more broadly — in all areas of life — children encounter participatory practices, and the more extensively and effectively adults open this space for them, the more quickly their maturity develops.

How Can Adults Open This Space?

Discussions on how to ensure participation often begin and end with the identification of methods. Similar to Turkey’s tradition of handing over state offices to children on April 23rd (National Sovereignty and Children’s Day) (Arın, 2015). One-off activities or single methods are an important part of participatory processes, but only a part. For this reason, specific methods form only a portion of the participatory process; in addition, the purpose and context must also be taken into account (Involve, 2005).

In short, if we were to formulate the key elements of participation:

Purpose + Context + Process = Outcome.

However, there is no simple formula or “ready-made” solution for successfully fostering participation. The choice of participatory methods should be made within the general design of effective participatory processes — whether short-term or long-term, specific or comprehensive — and depends on understanding both the context and the ways in which participation can be successful (Involve, 2005).

Sherry Arnstein (1969) famously said: “The idea of participation is like eating spinach — nobody is against it in principle because it’s good for you. In theory, citizen participation in decision-making is the cornerstone of democracy” (Arın, 2015). However, the point here is not that we need more participation, but that we need better participation. Better participation requires a better understanding of the complexities and the conflicts between people/children in the decision-making and implementation processes, enabling reconciliation (Involve, 2005).

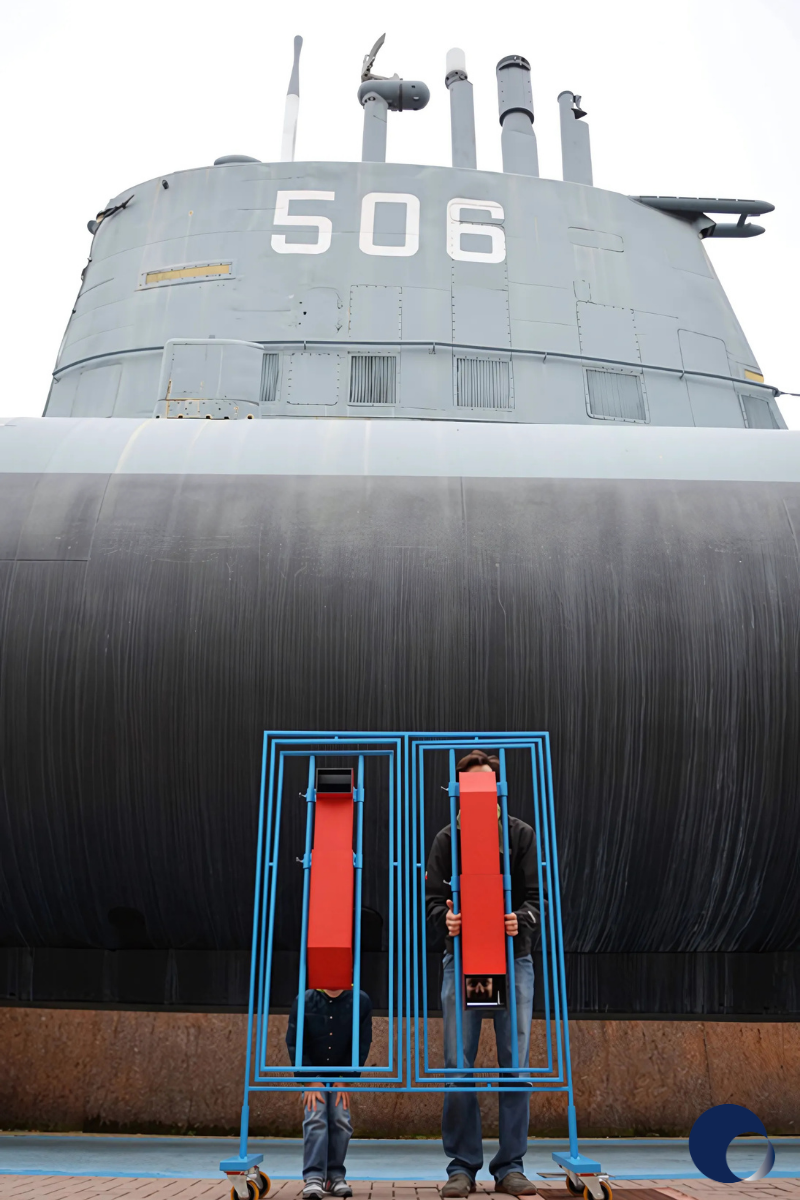

In recent years, there has been an increase in creative research methods through which children can inform or directly engage in the design process. These methods, aimed at gathering design-oriented information from young users, come with certain practical challenges and considerations when conducting design research with children (Süner & Erbuğ, 2014). With the growing prevalence of inclusive design, both globally and in Turkey, theoretical studies have begun focusing on issues related to child-friendly cities, playgrounds, and the physical and social environments they offer, and — albeit to a limited extent — these have been reflected in practice (Bayraktaroğlu & Büke, 2015; Uslu et al., 2016). An example of a good practice from these efforts is the “Play Knows No Barriers” project implemented by Bursa Nilüfer Municipality (Arın, 2015).

Conclusion

The “design for all” approach is a tool for ensuring that the built environment is inclusive for everyone. Creating a society that includes all is as much the responsibility of architects as it is of rights-conscious administrations. Adapting to changing needs over time now means making environments user-friendly regardless of the user’s age, gender, or ergonomic characteristics (Gökmen, 2009).

Participation enables children to express their opinions, needs, and demands regarding matters concerning them, to see themselves as individuals, and to play a decisive role in their own lives. Therefore, the true protection of children — ensuring that they can live and develop in a physically, mentally, and emotionally healthy manner — is only possible if their participation is ensured (Kılıç, 2015).

Ensuring inclusivity in designs for children, as Karaca (2018) notes:

“A child is nature itself. Holding within them the knowledge they need, and with a wildness that the adult world struggles to understand… But if we open our eyes and truly observe; if we hear the sounds reaching our ears not as noise, but as a cacophonic melody; if we put aside the words of experts and cultural patterns to feel with our hearts, this wildness will lead us to another world where we will begin to see and recognize ourselves. Then, we will cease to be arrogant teachers and become students learning alongside children.”

Content: Tasarım Group